‘Fiscal cliff’ legislation and retirement benefits: 2013 explained

Earlier this month, Senate and House passed, and the President signed, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. The new law avoids the ‘fiscal cliff’, which would have triggered significant tax increases this year for most taxpayers.

In this article we discuss the effect of the new legislation on retirement savings tax incentives.

Roth conversions

One provision of the legislation has a direct effect on retirement plans: under the legislation, qualified plans that maintain a ‘Roth option’ may allow a transfer of assets from a non-Roth account to a Roth account, triggering current taxation. In effect, participants are allowed to do an ‘in-plan Roth conversion.’ This provision was included in the legislation in order to ‘pay for’ the 2-month delay of the ‘sequester’ (a fancy term for mandated government spending cuts.)

Impact on retirement savings tax incentives

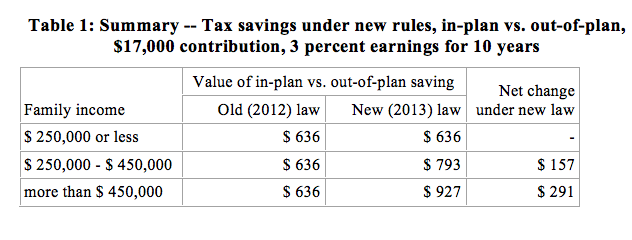

We have posted a series of articles analyzing the impact of possible tax law changes on the value of retirement savings tax incentives — the relative value of saving in a tax qualified plan (e.g., a 401(k) plan) vs. saving outside a plan. How has the new law changed that equation — changed the relative value of in-plan vs. out-of-plan savings? The following table provides a summary of the impact of the new legislation in that regard (assuming a $17,000 contribution left in the plan for 10 years and earning a 3% return) for three different types of taxpayers:

A family making $250,000, for whom the ‘old’ (2012) rates apply (top income tax rate of 35%; capital gains rate of 15%.)

A family making more than $250,000 but not more than $450,000, for whom the old rates apply, except that taxes on investment income increase 3.8% based on the new Medicare tax on net investment income.

A family making over $450,000, for whom the top income tax rate increases to 39.6%, the capital gains rate increases to 20%, and the new 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income applies.

Thus, the new law enhances the relative value of in-plan savings for certain high income taxpayers in 2013. In the remainder of this article we provide a detailed analysis.

Methodology

We begin with a discussion of our basic methodology — calculating the value of a participant’s plan contribution vs. saving outside the plan, for a period of 10 years. Our basic assumption is a taxpayer paying federal ordinary income taxes at the highest marginal rate. That participant is considering making the maximum contribution to a 401(k) plan — $17,000 in 2012. (We are continuing to use the 2012 401(k) limit so that we can do an apples-to-apples comparison of old law/new law tax effects. The 2013 limit is $17,500. As in prior articles, we’re going to ignore catch up contributions.) The contribution goes into a non-taxable trust. When the contribution and any trust earnings are paid out, the taxpayer pays taxes on the entire distribution at ordinary income tax rates (we are also ignoring additional taxes that may be due on premature distributions.)

Our questions are, generally, how much is the favorable tax treatment that 401(k) plans get under the Tax Code worth to this participant, and, specifically, how has the answer to that question changed under the new legislation? To answer those questions, we are going to compare the relative value of the tax benefit under the old law (our “base case”) and under the new law. Generally, we assume that:

The taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is the same in the year of contribution and the year of payout.

The trust earns 3% per year.

The money remains in the trust for 10 years.

We assume that the participant invests out-of-plan savings in capital gains-generating investments and that the full amount of capital gains is taxed each year at the (lower) capital gains rate (under current rules, you would get the same result if you invested in dividend producing stocks). (A “buy and hold” capital gains strategy — where no capital gains were realized until the end of the 10 year period — would produce a slightly better tax result for the out-of-plan saver.)

We ignore Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (Social Security and Medicare) payroll taxes, since FICA taxes are paid regardless of whether the participant saves in the plan or outside it. We will have to consider, when we come to the effect of the new legislation, however, the new Medicare tax on net investment income.

Base case

Under old-law rules, the key tax rates that affect the analysis are:

Ordinary income tax rate: 35%.

Capital gains tax rate: 15%.

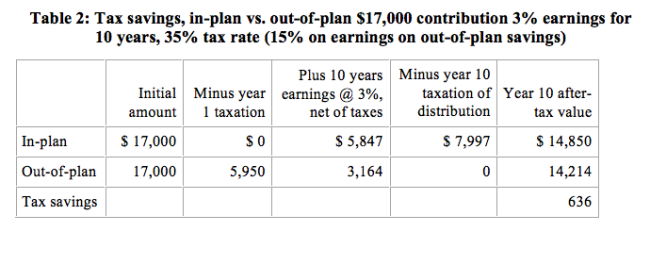

Based on those assumptions, here is the relative tax value of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. saving outside the plan under old law rules.

Thus, under old law rules, and assuming that out-of-plan investments maximize capital gains treatment, the participant would be $636 better off if she saved through the plan rather than outside the plan. This is also the result under the new law, in 2013, for families making $250,000 or less (assuming they are paying the top rate applicable to families below that income threshold, 35%.)

How the fiscal cliff legislation changes this result — families making over $450,000

Now let’s consider what happens, for top earners, after the passage of the fiscal cliff legislation. Here are the key changes in the new law:

Top income tax rate: 39.6% (for families making more than $450,000).

Capital gains and dividend tax rate: 20% (for families making more than $450,000).

New Medicare tax on net investment income: 3.8% (for families making over $250,000).

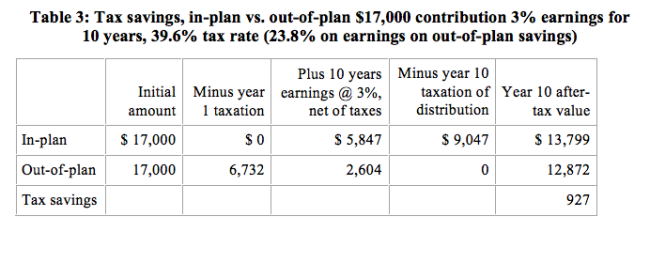

The following table shows the relative value of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. outside the plan for taxpayers in this group.

Under these rule changes, the relative value of saving in the plan increases from $636 to $927, an increase of 46%. Thus, post-fiscal cliff, saving in the plan is (relatively) a better deal for taxpayers in the new “top bracket.”

Families making over $250,000 but not over $450,000

Families making more than $250,000 and less than $450,000 fall in between these two cases. Like those making $250,000 or less, they will pay income and capital gains taxes at the old rates (35% for ordinary income and 15% for capital gains). But, like those making more than $450,000, they will pay the new 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income.

The following table shows the relative value of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. outside the plan for them.

Thus the new Medicare tax on net investment income increases the value of in-plan savings for this “in between” group by $157, a 25% increase in the value of the plan.

Impact of PEP and Pease phase-out

The new legislation “restores” provisions of the Tax Code that phase out the value of personal exemptions (the personal exemption phase-out or PEP) and a portion of itemized deductions (the so-called “Pease Amendment”) for families with adjusted gross income of more than $300,000. We have not included this provision in our analysis — its impact is very fact-dependent (for instance, on the size of the taxpayer’s family and the amount of itemized deductions).

We note, however, that the two phase-out provisions are keyed to an adjusted gross income (AGI) threshold. AGI is total income minus certain adjustments, including certain qualified plan contributions; 401(k) contributions are excluded from AGI. So, depending on how significant a taxpayer’s personal exemptions and itemized deductions are and how much income the taxpayer has, 401(k) contributions may reduce the phase-outs and thus further increase the tax value of saving in a 401(k) plan.

* * *

So, for high earners, the new legislation generally makes saving in a 401(k) plan more attractive than under the old rules. For those making $250,000 or less there is generally no change.