Distributed ledger technology and retirement savings infrastructure – part 1

Retirement plan sponsors are under constant pressure to reduce costs. In an era of decreasing investment returns and limited budgets, investment and administrative overhead is a target of management, policymakers, regulators and litigators. The bleeding edge of all this is the near-tsunami of 401(k) plan fee cases brought against plan fiduciaries over the last 10 years.

In response, sponsors and providers have sought to lower costs by leveraging scale (where available), “institutionalizing” plan investment (e.g., increasing use of collective trusts and separate accounts) and simplifying plan design. The movement (among some sponsors) towards explicit pricing (unbundling of investment and administrative services) and lower-cost passive investment strategies is also a response to this pressure.

These initiatives are all taking place within the current asset management and plan administration infrastructure, more or less at the margin. There is, however, an innovation emerging which some argue will radically change (more than one observer has used the word “revolutionize”) current infrastructure and materially reduce both investment and administrative costs across the board: distributed ledger technology (DLT). (Terminology in this area is still a little slippery. DLT is sometimes referred to as blockchain, although blockchain is just one type of DLT.)

Our goal in this and the following article is to open up discussion about DLT and its implications for retirement savings. In this article we review what DLT is. In our next article we will discuss possible implementations of DLT that could change (or “transform”) retirement savings plan administration and then consider some of the policy and legal/ERISA issues that the implementation of DLT may present for sponsors and providers.

A word of caution at the top: DLT is (obviously) an emerging technology/set of solutions. We write about retirement plan regulation and policy. We are writing about DLT – primarily – because it will affect (perhaps profoundly) retirement plan regulation and policy. Doing so, however, necessarily (given the current state of knowledge on the topic) requires a discussion of DLT itself and of how it may be implemented in the retirement savings context. In that regard, we are not experts, and those who want to develop a more thorough understanding of these issues will want to review the primary literature. Moreover, everything we say should be taken as provisional: the technology, its implementation and the regulatory and policy challenges they present will almost certainly change as we gain experience.

What DLT is –

Marc Andreessen (co-founder of Netscape) famously wrote that “Software is eating the world.” One way to think of the application of DLT to financial services and to retirement plan administration is as an instance of that maxim: DLT has the potential to “eat” the current (aka legacy) financial and retirement administration systems.

Where all of the data necessary for a securities transaction is digitized (where the cash is/who owns it and where the security is/who owns it), where all elements/steps in the transaction, e.g., authentication and authorization, can be implemented and verified digitally, end-to-end handling of the transaction can all be provided by software, alone, faster and at a significantly lower cost than it can in the current/legacy system.

Think of it as our world’s self-driving car.

Basic DLT components

In its paper on the topic, the Federal Reserve describes DLT broadly as: “some combination of components, including peer-to-peer networking, distributed data storage, and cryptography that, among other things, can potentially change the way in which the storage, recordkeeping, and transfer of a digital asset is done.”

As implemented, DLT arrangements may range from the incremental – the adoption of “a few of the key components of DLT as an enhancement to … existing technical platforms” – to the transformational – “replac[ing] entire functions traditionally managed by existing financial intermediaries … in very extreme but unlikely scenarios, the use of banks to conduct payments could become obsolete.” (Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C., Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Distributed ledger technology in payments, clearing, and settlement, Mills, Wang, Malone, Ravi, Marquardt, Chen, Badev, Brezinski, Fahy, Liao, Kargenian, Ellithorpe, Ng, and Baird. 2016-095. Hereafter, “Fed 2016.”)

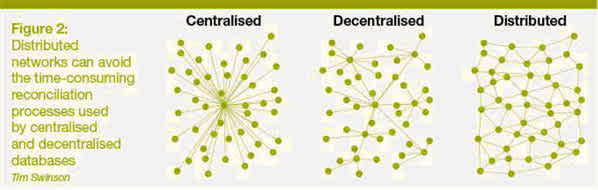

The following figure, taken from the Report by the UK Government Chief Scientific Adviser, Distributed Ledger Technology: beyond block chain, 2016 (hereafter, “UK Science Adviser 2016”), is a typical representation of the current system (on the left) and DLT (on the right):

The report describes how a distributed ledger can be used to reduce friction in banking:

Every bank has built or bought at least one (usually several) systems to track and manage the lifecycles of their financial transactions. Each of these systems cost money to build and even more to maintain. They must be connected to each other and synchronised, usually through a process known as reconciliation. This involves teams of people in each bank checking with their counterparts in other banks to make sure everything matches, and to deal with the problems when it does not.

A common solution involves setting up a single, centralised ledger shared by all participants. … But centralised utilities are typically expensive and, as their data and processing is centralised, they often must be integrated with each participant’s own systems. Alternatively, many decentralised databases can sit around the edges of a network while messages move between them [as in Figure 2].

Bitcoin, in contrast, synchronises thousands of computers in a distributed network via the internet: if my computer thinks that I own a Bitcoin, then so does every other computer in the network. If a similar technique could be used in banking, all the banks’ systems could stay in step with each other without requiring armies of people to reconcile and resolve the issues. Crucially, we do not need Bitcoin to achieve this – it is the underlying distributed ledger technology that offers a possible solution.

The application of this solution to 401(k) plan recordkeeping is obvious.

Hallmarks of DLT

The hallmark characteristics of DLT are: “reconciliation through cryptography, replicated to many institutions, granular access control, and granular transparency and privacy.” (UK Science Adviser 2016.)

Unlike current recordkeeping/custody systems, in which the “golden ledger” is kept by a central authority (e.g., a trustee/custodian or a plan recordkeeper), in a distributed ledger system the ledger is distributed to all participants in the network. In effect, everyone has a true, real-time copy of the ledger.

DLT vs. Bitcoin

DLT got its start in the development of Bitcoin and its associated blockchain ledger. Bitcoin uses an unpermissioned DLT (that is, the ledger is open to everyone and cannot be owned), and participants in it are anonymous (or at least pseudonymous), with the result that it has sometimes been associated with illegal activities (money laundering and drug trafficking).

Implementations under consideration in the financial services industry generally involve permissioned DLTs, in which, for instance:

[S]ome participants may only be permitted to … send and receive asset transfers for existing assets. Other participants may have the ability to issue new assets. Still others may have permissions to validate transactions …, while another set of participants may be able to update the history of transactions to the ledger …. Some participants may be limited to only reading the ledger, while others may also be allowed to write to the ledger. (Fed 2016.)

This structure may allow adaptation to current (legacy) processes under which, e.g., a selected person or group of persons has authority to validate information or transactions.

Moreover, for a variety of reasons (very much including compliance with Know your Customer and anti-money laundering rules), financial services DLT implementations would not be anonymous – although, as we will discuss in a subsequent article, the issue of confidentiality of information presents special issues in a distributed ledger.

The DLT “vision”

In an idealized DLT world, securities transactions would be proposed, executed and settled primarily through the use of software rather than physical/human intermediaries: “reconciliation through cryptography.”

Information about the transaction would then be distributed to the ledger: “replicated to many institutions.”

This distributed ledger would hold all the information about this (and all other) transactions, providing “granular access control and granular transparency.”

Confidentiality would be implemented via cryptography – only those with permission would be able to decode ledger data (or specific elements of ledger data). But it is important to remember that all the data is still there in the distributed ledger. Whether a particular participant (or regulator or competitor) is able to see it would be determined/implemented through cryptography and permissions (“keys”).

Most agree that the likely path to this ideal (if there is one) begins with incremental improvements in current processes.

Technical issues/further reading

We’ve skipped over a lot of significant DLT engineering issues: How does the cryptography work? How does the data get distributed and then held securely? Who makes decisions (minimally) about the terms of the software and how participants (in the network) interact with it? And, obviously, many more.

A number of financial services institutions and regulators are working on and exploring these issues in connection with the implementation of DLT. For further reading, the two papers referenced above, from the Federal Reserve and the UK Chief Scientific Adviser, are as good place as any to start. We’ve also provided as an Appendix a set of definitions of some basic terms, excerpted from the UK Chief Scientific Adviser’s paper.

* * *

In our next article we will consider what the implementation of DLT could mean to retirement savings plan administration and some policy and legal issues it may present.