DC target date performance 2021-2023, in four charts

Over the coming weeks we are going to review the effect of 2023 financial market performance on DB plans generally and consider its implications for three critical issues in 2024 – lump sums (and lump sum windows), the standard vs. alternative method election (for purposes of calculating PBGC premiums), and funding relief (or lack thereof). But before we do that, we want to consider the effect of the last three years of financial market performance on DC plans/participants and the DC retirement income equation.

DC retirement income finance

Financing retirement income is, in most respects, relatively intuitive for DB plan sponsors, who have been living with an accounting regime that requires them to book asset and interest rate performance to the balance sheet currently.

In a DC plan, the performance of a participant’s “pile of assets” is also very intuitive – it operates like a brokerage account. But the significance of changes in interest rates is more obscure … until the participant starts thinking about retiring and about how much income he will need to cover expenses. Because interest rates (as it were) describe the “price” of income – how much it will cost to turn a pile of assets into income (to pay for expenses). That obscurity is in part why it has been so difficult to get participants interested in a “retirement income solution” for DC plans.

Key financial variables for a participant nearing retirement

We’re going to focus on a participant who is 55 years old at the beginning of 2021, looking to retire at age 65. As of January 1, 2021, he has enough money – $161,627 – to buy a deferred-to-65 annuity of $1,000 per month. How has he done over the last three years, that is, since January 1, 2021?

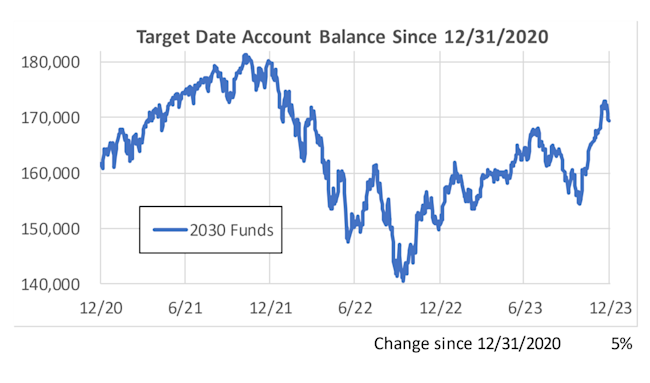

Asset performance – low single-digit return on the TDF’s 2030 fund over the last three years

Let’s start with the asset side. Over the last three years, this participant’s account, invested in his plan’s 2030 TDF, has grown to $169,485. His asset pile has produced “minimal” returns: up just 5% in three years. Not good. (Note, for this purpose we averaged returns on the three top public target date funds.)

The impact of inflation

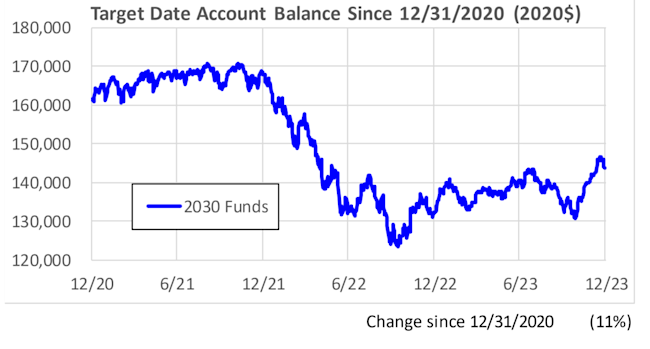

But it’s even worse than that, because this three-year period saw the return of inflation (CPI increased 17.8% between December 2020 and December 2023).

Adjusting for inflation, the value of the account balance at December 31, 2023 (in 2020 dollars) is only $143,776. That’s an 11% decline in purchasing power. If the participant wanted to withdraw his money to buy widgets, he could buy 11% fewer widgets at the end of 2023 than he could at the end of 2020.

So we gone from not good to worse.

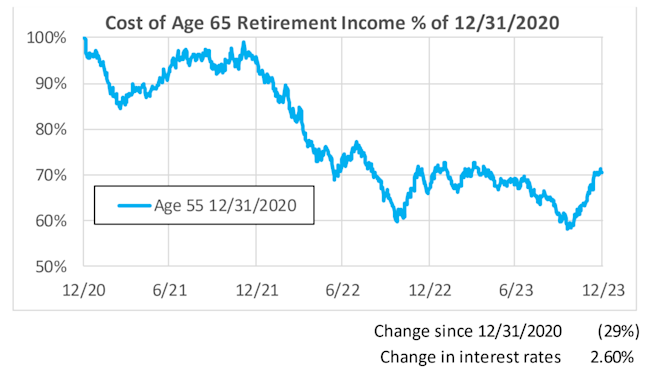

The cost of (retirement) income, however, has gone down – a lot

But this money isn’t for buying widgets, it’s for buying retirement income. And interest rates are up 2.6% since the end of 2020 (much of the reason for the poor asset performance), reducing the cost of retirement income by 29%.

This is an extraordinary gain for our participant.

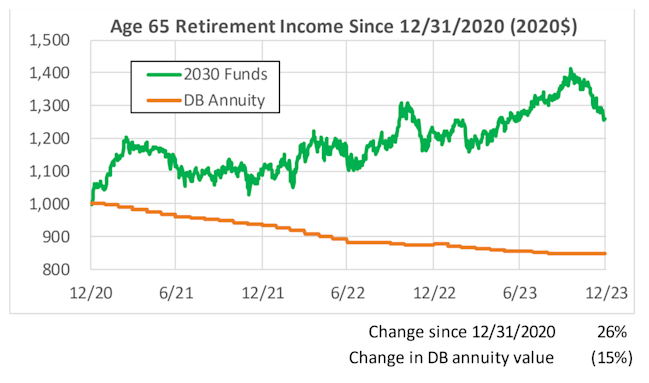

A 26% improvement in the participant’s retirement income

When you put it all together, the 2030 fund has increased the real lifetime income at age 65 the participant can buy with his pot of money by 26% over the past three years.

What is going on here?

In thinking about the DC participant’s project of financing retirement income, we need to consider several factors:

Losses/poor performance of equities and bonds is (as in 2022) often correlated with increases in interest rates. This is largely because, as the discount factor (interest rates) goes up, asset values go down.

For those looking to convert an asset pile into income, however, high interest rates are good news. And to be clear, it’s not just bonds we’re talking about – higher interest rates mean higher expected returns to capital generally (i.e., including higher returns on equities).

Obviously, the sweet spot (for an investor whose ultimate goal is to produce income) is any case in which the “income gains” from higher interest rates are greater than “asset losses.”

The capital markets participants are heterogeneous. Entrepreneurs and investors whose goal is “capital gain” – to build/invest in a growing business – prefer low interest rates and a big pile of money. But retirement savers prefer high (real) interest rates and high returns to capital. The investment strategy/goals of the latter (retirement savers) is fundamentally different from the former (growth investors). What’s good for one may be bad for the other, and vice versa.

The joker in all of this is inflation. In an inflation-free world, the risks that a retirement saver approaching retirement faces could all be solved with a fixed income portfolio. DB sponsors live in that world – their retirement income promise is strictly in nominal dollars. DC participants don’t. The only solutions they have available to deal with inflation risk are very expensive – Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) or an inflation-adjusted annuity (if you can find one). It would seem (in considering the experience of the last three years) that equities may provide some resilience vs. non-inflation protected bonds (which have a mathematically defined vulnerability to inflation).

Takeaways

From all this, we can’t draw any simple spread-sheet driven conclusion. Diversification still remains critical, even as a participant approaches retirement. The bundle of risks the participant faces, however, change. As the participant approaches retirement:

Volatility matters more. A 20% decline in portfolio value is much harder to recover from if, instead contributions going in, money is going out of the portfolio (as retirement income).

Inflation is an acute risk with respect to bonds and annuities – less so with respect to equities.

Prior to annuitization (or prior to putting the entire portfolio into bonds), the real questions is, the performance of the asset portfolio vs. changes in the cost of income. To only look at the size of the participant’s pile is a mistake.

The “rotation toward fixed income” inherent in current target date fund investment practice as a participant approaches retirement to some extent stabilizes the nominal retirement income produced by the portfolio, although this effect is dependent on the duration target date fund’s bond portfolio.

The older (55+) participant’s portfolio should reflect these concerns.