Reducing pension plan headcount reduces risk and PBGC premiums

Background – de-risking in 2014

Last December, we published an article discussing the strategy of offering lump sum payments to deferred vested pension participants during 2014. Since then, three things have happened to underscore the value of this strategy:

Interest rates have gone down this year, increasing the cost of paying lump sums in 2015 as compared to 2014

A new mortality table from the Society of Actuaries is likely to be adopted by the IRS for pension plans in the next couple of years, increasing the cost of lump sums

More pension funding relief, which clears the way for many less well funded plans to pay lump sums during 2014

As discussed below, the reduction in PBGC variable premiums for underfunded plans that cash out terminated vested participants can be enormous, because of the operation of the PBGC’s ‘cap’ on variable premiums.

Lower interest rates

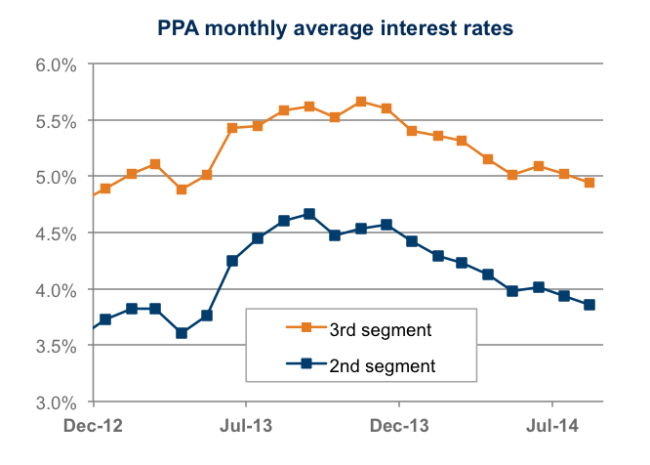

The chart below shows the movement of long-term interest rates since December 2012, based on changes in the ‘PPA segment rates’ which are used for pension lump sum calculations:

As the chart shows, rates peaked around the end of last year. This is significant for a couple of reasons.

When a DB plan pays a lump sum, the amount of that lump sum must generally be calculated (converted from an annuity beginning at normal retirement age) based on ‘spot’ segment rates. Many sponsors set their plans’ lump sum rates at the beginning of the year, based on prior year November interest rates, so that participants will know what rates will be used to calculate lump sums for the entire year.

The table below shows spot segment rates for November 2013 and current spot segment rates.

First Segment | Second Segment | Third Segment | |

November 2013 | 1.19% | 4.53% | 5.66% |

July 2014 | 1.26% | 3.94% | 5.02% |

The critical medium- and long-term rates are around 60 basis points lower now (that is, as of July 2014) than they were in November 2013. So, for plans using a November 2013 rate for 2014 lump sums, a lump sum can be paid out, in effect, at a discount.

And, if interest rates in November 2014 are the same as current rates, then the lump sums in 2015 will be a lot more expensive than in 2014 – for a 45 year old, the lump sum at 1/1/2015 would be 20% higher than at 12/1/2014, and the difference is even greater at younger ages.

New mortality table

The second factor, revised mortality tables, may perhaps have even more long-run significance. As we discussed in our article ”New mortality table recommended by Society of Actuaries,” the Society of Actuaries has proposed new mortality tables that may significantly increase lump sum valuations. The SOA proposal has generated some controversy (see our article ”Actuarial group raises questions about proposed RP-2014 mortality tables”). It has been reported that the SOA will likely release updated tables by October 31, 2014. And updating mortality tables has been included in IRS’s 2014-2015 Priority Guidance Plan. After revised mortality tables are adopted by IRS, paying out lump sums is likely to be more expensive, perhaps as early as in 2016.

Finally, as we discussed in our article ”Concerns over pension de-risking,” opposition by participant advocate groups to at least some forms of de-risking is building.

* * *

In the rest of this article we’re going to discuss another factor that may make paying out lump sums to terminated vested participants particularly attractive for underfunded plans: the potentially huge reduction in Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation variable-rate premium costs.

The PBGC variable-rate premium and the headcount cap

As we discussed in our prior article on the subject, paying out terminated vested participants obviously reduces the PBGC flat-rate, per capita premium – fewer participants equals fewer ‘heads to count.’ But the gains are relatively modest – $64 per year per participant in 2016. While less obvious, the gains in reduced variable-rate premiums can be much more significant. Those gains come from the headcount-based cap on variable rate premiums.

How the headcount-based cap works

Calculation of the variable-rate premium is a two-step process:

1. The first step is to multiply the applicable dollar amount times each $1,000 of unfunded vested benefits (UVBs). UVBs are, generally, the plan’s liabilities for vested benefits minus the fair market value of plan assets. Liabilities for this purpose are determined using “spot” PPA first, second and third segment rates, but without the interest rate stabilization provided by 2012’s Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) and 2014’s Highway and Transportation Funding Act (HTF 2014).

The following chart shows the “applicable dollar amount:”

Plan years beginning in | Rate per $1,000 UVBs |

2013 | $9 |

2014 | $14 |

2015 | $24 * |

2016 | $30 * |

(*Estimated. Rates after 2014 are adjusted up for wage inflation.)

The calculation in step 1 sounds a little more complicated than it is in practice. Oversimplifying, you take liabilities for vested benefits, subtract plan assets, divide by $1,000 and then multiply by, e.g., for 2015, $24. For example, if the plan had $50 million in UVBs in 2015, the amount determined under this step 1 would be $1.2 million – $50 million divided by $1,000 times $24.

2. The second step applies a headcount limit to the amount derived in 1. The total amount a sponsor must pay in variable-rate premiums is limited to the plan’s total number of participants (determined as of the close of the prior year) times a per participant cap. The following chart shows the “per participant cap:”

Plan years beginning in | Per Participant Cap |

2013 | $400 |

2014 | $412 |

2015 | $425 * |

2016 | $500 |

(*Estimated. After 2016, the cap is adjusted up for wage inflation.)

Let’s go back to our example of a plan with $50 million in UVBs in 2015, which generated a step 1 variable-rate premium number of $1.2 million. If at the end of 2014 there were 1,500 participants in the plan, then the maximum variable-rate premium the sponsor would have to pay with respect to the plan would be $637,500 – 1,500 times $425 per participant – not $1.2 million.

While all of this is complicated, it should be clear that, once a certain threshold is reached, lower headcount translates directly into lower variable-rate premiums. Thus, paying lump sums to terminated vested participants may, depending on your plan demographics and funded status, dramatically reduce your variable-rate premium.

Example

To illustrate just how significant this can be, let’s work through an example.

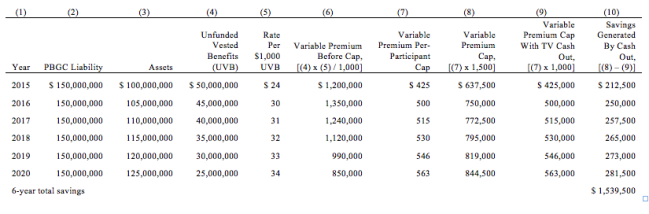

Assume a plan has $150 million in liability, $100 million in assets and 1,500 participants, 500 of whom are terminated vested participants. The following table shows the total variable premium paid over the period 2015-2019 if the plan does or does not pay out all 500 terminated vested participants in 2014.

This example is very oversimplified – assets and liabilities are not adjusted for benefit payments or the time value of money, although we do assume annual contributions of $5 million to reflect the expected pattern of improving funded status.

Relationship between premium cap and funded status

If we compare column (6) to column (8) in the above example, we see that the variable premium cap is expected to apply to this plan through 2020. Note that this is only because the plan is significantly underfunded ($50 million). If assets were $125 million, the cap would not apply in any of these years. Clearly, the larger the plan’s unfunded liability, the more likely the variable premium cap is to come into play.

Note that the plan in our example is only 67% funded ($100 million / $150 million). Ordinarily, plans that are less than 80% funded cannot pay lump sums to participants, but this is where pension funding relief comes in.

As we discuss in our article on the extension of pension funding relief, many underfunded plans will report a funded status of 80% or more in 2014 due to the higher rates used to measure pension liabilities (which don’t affect the calculation of PBGC liabilities), clearing the way to offer lump sums to terminated vested participants this year.

In our example, the employer enjoys PBGC premium savings of more than $1.5 million over the next six years – on top of the de-risking benefit – by cashing out terminated vested participants in 2014.

Effect on funding

A possible unintended consequence of cashing out terminated vested participants is that it will increase a plan’s ‘funding shortfall’, and required contributions, in the following year. Why is this?

Returning to our example, suppose the plan pays out $25 million to terminated vested participants during 2014. Both the assets of the plan and the PBGC liability decline by about $25 million, since the basis for measuring PBGC liabilities is essentially the same as the basis for paying lump sums.

For minimum funding purposes, however, the plan’s liability in 2015 is quite a bit lower (probably about $120 million rather than $150 million) because of the higher ‘funding stabilization’ interest rates. So, paying out terminated vested participants may only reduce this liability by, say, $20 million. Since assets are $25 million lower, this translates to an increased funding shortfall in 2015 of $5 million, and an increase in 2015 required contributions of close to $1 million.

Sponsors will want to keep in mind, however, that while plan funding costs may go up because of a payout to terminated vested participants, plan funding – in effect, paying for benefits under the plan – is something the sponsor will (absent exceptional circumstances) have to do anyway, and any additional contributions made now will reduce contributions needed in the future.

In contrast, PBGC premiums function more like a tax. Unless your plan ultimately goes through a distress termination, the premiums you pay go to fund other companies’ benefits.

Thus, reducing PBGC variable-rate premiums reduces real costs; increasing funding simply accelerates the payment of costs you will, at some point, have to pay in any case.

Alternative strategy – borrow and fund

As we have discussed in the past, a more straightforward strategy for reducing PBGC variable premiums is to simply accelerate pension funding – see our article ”PBGC variable premium vs. borrow-and-fund: impact of higher premiums”. As noted, increasing funding reduces the effect of the per participant variable-premium cap and thus is generally an alternative, rather than a complementary, strategy to paying out lump sums to terminated vested participants. Borrowing-and-funding may, however, for some companies be the better strategy.

* * *

If you’ve stuck with the analysis this far, it should be clear that there are a lot of moving parts to the foregoing analysis. Pension sponsors can expect PBGC premiums to triple or quadruple in the years ahead, making these premiums a major source of overhead cost for plans, unless sponsors adopt an aggressive approach to managing these costs.