Markets 2020: settling DB plan liabilities

In February, we posted an article reviewing (generally) the economics of paying out a lump sum to a deferred vested participant in 2020, in which we analyze de-risking in terms of the cost/cost saving with respect to a terminated vested 50 year-old individual who is scheduled to receive an annual life annuity of $1,000 beginning at age 65.

One critical factor in that calculation is the cost of the lump sum, which (for most plans) is generally a function of an interest rate set before the beginning of the 2020 plan year. In our example we use a November 2019 valuation interest rate for 2020 lump sum valuations, which in our experience is the most common month used.

One of the factors to consider in deciding whether or not to de-risk in 2020 is the difference between current (corporate) valuation interest rates and that November 2019 valuation rate. Since our February 2020 article, corporate rates have been on a wild ride – increasing to almost 4% before falling back to (almost) 2.5%. In addition, there has been a reduction in economic activity of significant but (at this point) indeterminate scope. And there have been unprecedented federal monetary and fiscal stimulus efforts, in the trillions of dollars, and it remains unclear whether and how these efforts will affect future interest rates (and, relatedly, future inflation and economic growth).

Four key datapoints

In this article we focus on the critical issue (for the de-risking decision) of interest rates. This is a complicated issue, with a lot of moving parts. And it is only one element of the de-risking decision.

So, we want to begin with a summary of what we view as the four most important datapoints for the 2020 de-risking decision:

1. Lump sum valuation rates generally are more favorable than current market rates. Current interest rates are more than 50 basis points lower than the November 2019 rates used (in our “typical” plan) to value lump sums, so paying out a lump sum now (end-of-April 2020) produces a “gain.” That is, if rates remain at these levels, the spread between the cost of the lump sum vs. the value of the liability will show up as an improvement on the 2020 balance sheet. For our example 50-year old terminated vested participant, that improvement will be around $1,600.

2. Savings in PBGC premiums may be considerable. As we discussed in our February 2020 article, the present value of savings from de-risking our example individual are $2,002 in Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation flat-rate premiums and, for sponsors subject to the variable-rate premium headcount cap, an additional estimated $2,676 in reduced variable-rate premiums. (We note that, with 2020 interest rate and asset declines, some plans that are not subject to the headcount cap in 2020 may be subject to it in 2021.)

3. Many participants need cash now and may be eligible for favorable tax treatment. DB lumps sums can provide a source of much needed cash for financially distressed participants, and there may be special tax benefits (for participants) incentivizing them to take a 2020 distribution. (See our article Implementing a Coronavirus distribution program in your DB plan.)

4. The one wild card facing sponsors is the direction of future interest rates. If a sponsor believes that there is a likelihood interest rates will go up in the near term (e.g., that the monetary and fiscal stimulus will kindle inflation), then it may wish to defer de-risking.

* * *

The balance of this article is about issue 4 – an in-depth analysis of the issue of interest rates and de-risking. Our intent here is not to predict the direction of future rates, but to identify the factors that may affect it.

We begin with a brief discussion of the de-risking equation.

The de-risking equation

To be clear about the framework of our analysis: by de-risking we mean (narrowly) settling a defined benefit liability currently, typically either through (for a deferred vested participant) paying out a lump sum or (for a retiree) purchasing an annuity.

The cost of either sort of transaction will depend primarily on (more or less current) interest rates. And the decision by a sponsor to de-risk now vs. de-risking in the future will depend in the first instance on the sponsor’s view of whether it will cost more/less to either (1) de-risk in the future (e.g., because future interest rates will be higher than current rates) or (2) simply hold the retirement liability in the plan and pay it out as the plan provides.

As we noted at the beginning, there may be other factors driving a de-risking decision – e.g., corporate capital or benefits policy and participant needs in the current crisis. Our focus in this article is, however, the “simple” economic decision captured by the de-risking equation – “will interest rates in the future be lower/higher than the rate at which I can settle liabilities currently.”

Rates and spreads

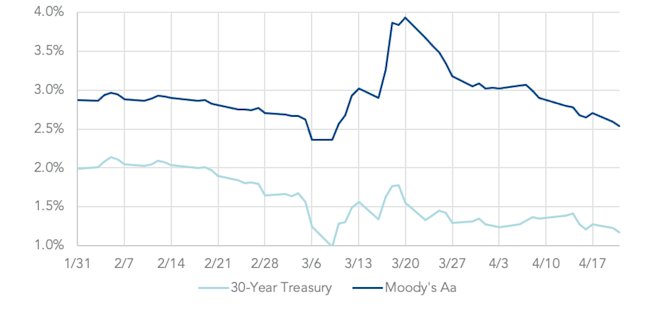

For the past decade, credit spreads moved in a narrow range, with Aa bond yields averaging about 1% above Treasuries, but last month markets saw by far the biggest movement in spreads since 2008. As Chart 1 shows, since early March corporate bond yields have gyrated wildly, increasing to almost 4% before tumbling back toward 2.5%.

Almost all of this volatility is attributable to fluctuating credit spreads, which soared to almost 2.5% before falling back below 1.5%. As the chart shows, the 30-year Treasury bond briefly fell below 1% in March before recovering somewhat, but it has remained near this all-time low since.

Chart 1Yields February 2020-present – Moody’s Aa long-term corporate/30-year Treasury

The experience over the past several decades suggests that elevated credit spreads – which are generally understood to represent a “flight to quality” – can persist for several years (e.g., throughout 1999-2002) or they can snap back quickly (as in 2009), but for the near future at least they are a variable to contend with.

Ultimately, we expect spreads to narrow at some point. The question is: will they “narrow up” (with Treasury yields moving higher) or “narrow down” (with corporate yields moving lower)?

History – long-run trend in interest rates

With regard to this question – the direction of interest rates, and the relationship between rates and spreads, following a significant negative market event – it may be useful to consider (1) the long-run trend of interest rates and (2) what happened to interest rates after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

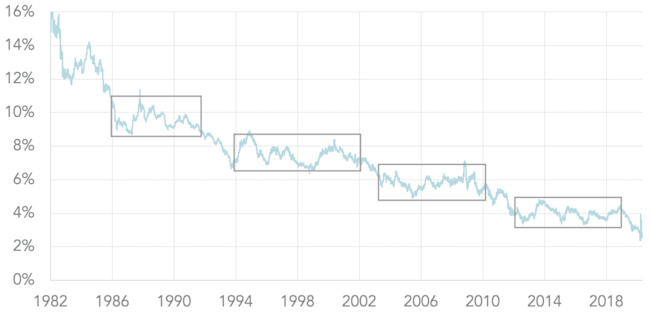

Chart 2 shows the long run trend in interest rates since 1980.

Chart 2Moody’s Aa long-term corporate bond yields 1982-present

As we have discussed in prior articles, the pattern appears to be periods (lasting as long as eight years – e.g., from 1994-2002) of relative stability, followed by an adjustment down, followed by another period of stability. We have “boxed-out” the periods of stability in the chart.

Chart 3 shows the last of these periods.

Chart 3Moody’s Aa long-term corporate bond yields 2012-present

A big question, particularly for DB plan sponsors for whom plan-related interest rate risk is a significant factor, is whether the lower rates we have experienced since the second half of 2019 represent a “new normal?”

History – rates and spreads after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

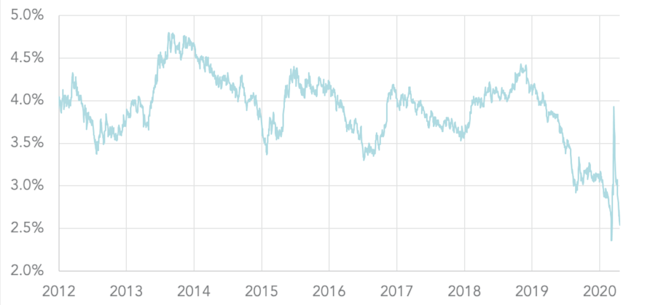

As we said at the top, the trajectory of future interest rates is likely to depend on what happens to credit spreads. Chart 4 shows the spread/relationship between 30-Year Treasuries and Aa corporates during the period immediately following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Chart 4Moody’s Aa long-term corporate/30-year Treasury 2008-2012

The pattern during this period was that in the short-run rates “narrowed up” – that is, Treasury rates increased both absolutely and relative to corporate rates. But in the long-run, rates generally reverted to the long-run downward trend.

Settling retiree liabilities with annuities

As we understand it, it is currently generally possible to settle a retiree liability (this emphatically does not apply to deferred vested liabilities) with an immediate annuity at something close to book value – that is, the value of the liability using current interest rates.

Thus, the analysis provided above with respect to lump sums may (with a number of qualifications) also apply to annuity settlements.

No bottom line yet

We provide the foregoing as a way of thinking about the question posed. We believe that in the current very fluid and volatile situation, providing a bottom line – de-risk/don’t de-risk – is premature.

* * *

We will continue to follow this issue.