New Challenges for Contributing Employers in Multiemployer Pension Plans – Is It Panic Time?

With equity markets down roughly 30% year-to-date (although that seems to change many times per day) and prevailing bond yields showing as much volatility as at any time since the passage of ERISA, employers that contribute to one or more multiemployer plans have to be wondering – should we be worried? Should we panic? Is there anything we can do?

In all likelihood, the answer is “it depends.”

In this article, we’ll lay out some of the problem situations employers who contribute to multiemployer plans may confront and explain what they are, what can cause particularly adverse financial consequences, and whether there is anything that can be done about them. For employers that contribute to these types of plans but don’t really understand them, we’ve provided a sidebar with some background. And we must provide a caveat: everything in this article should be considered to be generally applicable, but the rules and the calculations may vary significantly for specific situations.

* * *

Sidebar: multiemployer plan basics

A multiemployer pension plan, sometimes referred to as a Taft-Hartley plan, is a collectively bargained plan maintained by more than one employer, usually within the same industry, and a labor union. Contributing employers make contributions to the plan as negotiated in a collective bargaining agreement. Benefit levels for plan participants are usually set by the trustees of the plan, a group normally made up of half union and half management representation.

Employers in a plan are protected against other employers leaving the plan by a concept known as withdrawal liability. Oversimplifying, an employer that leaves an underfunded multiemployer plan owes money representing their share of the underfunding to the trust.

Just as is the case with traditional pension plans maintained by a single employer, some multiemployer plans are well-funded and some are not. The Pension Protection Act of 2006, including amendments since then, has established new classifications for multiemployer plans. Often known by their traffic light colors, yellow zone plans are considered endangered and red zone plans are considered critical. Certain red zone plans that are deemed by the plan’s actuary to be in significant danger of running out of money are considered critical and declining.

Generally speaking, yellow zone plans are required to adopt a “funding improvement plan,” while red zone plans must adopt a “rehabilitation plan.”

Withdrawal from a plan

There are three types of withdrawal from a multiemployer plan – complete, partial, and mass. Each has its own special set of rules.

An employer is said to completely withdraw from a multiemployer pension plan when the employer (including all controlled group members) permanently ceases to have an obligation to contribute to the plan or permanently ceases all covered operations under the plan.

An employer is deemed to partially withdraw from a plan when there is:

A decline of 70% or more in the employer’s “contribution base units” (CBUs), or

A partial cessation of the employer’s obligation to contribute.

A “CBU” is the basis on which an employer’s contribution requirement is determined, e.g., hours worked. A decline in CBUs is measured based on the reduction in CBUs for a 3-year period as compared to the highest 2 years period during a 5-year lookback.

The “partial cessation” test is intended to prevent an employer from reducing its obligation to contribute through, for example:

A situation in which an employer is obligated to contribute to the plan under multiple bargaining agreements, and one or more of the agreements expire, but the employer continues to perform work in the jurisdiction of the agreement without making contributions in respect of the work, or

A situation in which an employer ceases to contribute for one or more of its operations but continues to perform work at that facility.

A mass withdrawal occurs when all or substantially all employers completely withdraw from a plan.

* * *

The Current Economy

As we all know, since the effects of the coronavirus pandemic have begun to be felt, the economy has been in flux. From peak to trough over the last six weeks, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has fallen more than 30%, and other indices have performed similarly. Yields on 10-year Treasuries over the same period have ranged from a high of about 1.62% to a low below 0.40%. As we write, they sit at 0.92%. While they have not moved in lockstep, other bond yields have varied similarly.

What will happen over the rest of 2020? Who knows? We certainly don’t.

Key risks as we see them

The key risks, during these times of turmoil, for employers contributing to multiemployer plans are these:

A change in zone status resulting in a Funding Improvement Plan or Rehabilitation Plan

Layoffs and work stoppages causing a partial withdrawal in 2020

A business downturn causing the company to completely withdraw during 2020

An industry downturn causing a mass withdrawal in 2020 or (even) in the next 3 years

In what follows we discuss these risks in more detail.

Change in Zone Status

While there are technical details around zone status that can complicate matters, including a plan choosing to elect critical status, generally zone status is determined by a plan’s funded status. Without going to deeply into the rules, endangered plans have a funded status as reported on Schedule MB to Form 5500 of less than 80%. _Critical plans_have a funded status of less than 65%. Plans that have or could have an accumulated funding deficiency could also fall into endangered or critical status.

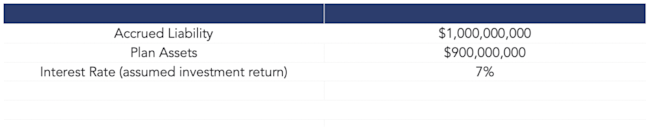

Could this happen to a plan in which you participate? Let’s consider fairly simple example based on a January 1, 2020, actuarial valuation to illustrate.

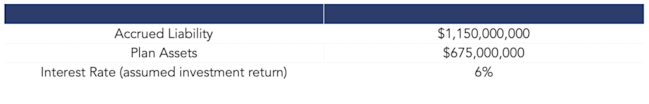

In this scenario, the plan is 90% funded (green zone) barring a projection of an upcoming funding deficiency. Now, let’s make a couple of changes based on events over the last few weeks. Assume that assets have lost 25%, and further assume that as a result of current market conditions that the plan’s actuary has reduced the plan’s interest rate from 7% to 6%. Finally, let’s give the liabilities of the plan a modified duration of 15.

Then, simply reflecting what the numbers in the chart above would look like if we reflected those events, we see:

In this scenario, the plan is now just less than 60% funded (red zone). Simply based on the events over about a 45-day period, the plan has moved from green zone to (theoretically) red zone or critical status. Recall that plans that are actually in critical status must adopt a rehabilitation plan.

Rehabilitation plans can take a number of forms. In our experience, they generally require that contributing employers make additional contributions to the plan. As a contributing employer, you may not have discretion (even if you do, it will usually be among a variety of plans each of which require additional contributions). If the rehabilitation plan adopted by the trustees requires additional contributions, then your costs will increase, at least temporarily.

Partial Withdrawal

Expanding a bit on the test we laid out previously, consider that an employer incurs a partial withdrawal (simplifying somewhat) if its CBUs for each of three years are less than 30% of the average CBUs for the two highest years of the five-year period immediately preceding the three-year period (confused yet?). So, a single year with a significant decline is not the problem that employers should concern themselves with. However, suppose you’ve been decreasing your union population and have been monitoring to ensure that you don’t have a partial withdrawal. With the effects of the pandemic, you might not be able to avoid one.

In a variation on this theme, suppose the pandemic causes extremely significant work reductions, and your industry or specific business does not recover sufficiently to resume normal working conditions – you could also be in danger of incurring a partial withdrawal.

Complete Withdrawal

Some companies, either as a result of current circumstances or because they had planned to anyway, may either choose to or be forced to completely withdraw from a multiemployer plan. The good news is that if you withdraw during 2020, and you are not part of a mass withdrawal (see mass withdrawal below), your withdrawal liability will be based on the status of the plan as of 12/31/2019 and on 2019 actuarial assumptions.

Sometimes, however, a withdrawal, even a planned one, cannot be completed as soon as you would like. In the event that you don’t completely withdraw until 2021 or are part of a mass withdrawal, your withdrawal liability calculations will, at the very least, reflect 2020 results.

Mass Withdrawal

Mass withdrawals typically only occur when there is a significant downturn in an entire industry. You will generally be the best judge of whether the industry or industries in which you operate is at risk for this in the current crisis.

If you are concerned that your industry is at risk of a mass withdrawal from a plan, you may not be able to avoid mass withdrawal treatment by trying to withdraw early, e.g., during 2020. Under ERISA, contributing employers that withdraw within the three years immediately preceding a mass withdrawal will be subject to additional reallocation liabilities that they otherwise might not have planned for.

Determining Withdrawal Liability

The calculation of withdrawal liability is one of the most complex concepts under ERISA. Each plan chooses from among the allowable methods of determining withdrawal liability. Then, the plan’s Enrolled Actuary performs a calculation using a variety of actuarial assumptions, the most important of which is often the interest rate assumption.

While that interest rate assumption is often the subject of dispute (when a withdrawing employer contests the determination of withdrawal liability, ERISA requires that the dispute first be arbitrated before it can be litigated in Federal Court), plan actuaries usually use one of several bases to select the withdrawal interest rate assumption

The investment rate of return used for minimum funding calculations (an October Three analysis of 680 multiemployer plans for the 2018 plan year showed that more than 70% of them assumed an investment return of at least 7% per year)

The investment rate of return (above) less a small margin (often 50 or 100 basis points)

A composite calculation often referred to as the Segal Blend (this assumes that assets for funded vested benefit liabilities have an investment return at PBGC rates while unfunded vested benefit liabilities have an investment return at the funding interest rate)

The current liability interest rate (based on an average of yields on 30-year Treasury bonds and currently set at a maximum in the vicinity of 2.9%)

Rates used by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) upon plan termination (these rates are mandatory for determining withdrawal liability in the event of mass withdrawal) – currently slightly above 2%.

Each withdrawing employer must pay its share of the unfunded vested benefit liability (UVB) determined using an interest rate like those in the summary above. Again oversimplifying, an employer’s share is roughly determined as the total UVB for the plan multiplied by a fraction whose numerator is the employer’s average CBUs for its highest three consecutive year period during the last ten and whose numerator is the total CBUs for the plan.

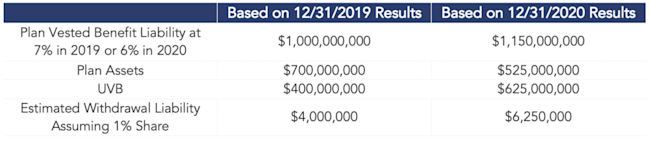

Let’s consider a very simple example for XYZ Company that will be completely withdrawing in 2021 from the ABC Plan:

The increase in withdrawal liability in this example is pretty startling but may well be typical. And, for worse funded plans than this using different actuarial assumptions, the calculation may be even more heavily leveraged, producing ever more disturbing results.

What Can Contributing Employers Do?

If the start of 2020 is any indication, this could be a very volatile year for plans of this sort. For employers in well-funded plans in strong industries, even funding improvement or rehabilitation plans that are put in place might be only very temporary. For poorer-funded plans in weaker industries, however, employers should consider their options (depending on your collective bargaining situation, they may be limited at most) and monitor the situation carefully. Here, your October Three consultants can help.

As a contributing employer, you might consider any or all of these possibilities:

Monitor estimated funded status under multiple scenarios

Monitor your CBUs to ensure that you do not (or do if you prefer) incur a partial withdrawal

Monitor projected withdrawal liability under as many scenarios as are appropriate for your level of risk tolerance

Clearly, this situation is highly volatile, and this analysis very much depends on what happens in the relevant markets.

* * *

We will continue to monitor developments, but please contact an October Three consultant to get assistance in evaluating your particular situation.