Plain talk about cash balance plans

In this article we discuss the risks to plan sponsors presented by a “traditional” cash balance plan — that is, a plan that provides interest credits based on an IRS-approved fixed income yield. We assume a general familiarity with how cash balance plans work.

Cash balance plans were developed in the 1980s as a ‘hybrid’ retirement plan. For employees, the design produces an easy-to-understand, account-based benefit that looks a lot like a defined contribution (DC) plan. For employers, these designs are less risky than the traditional defined benefit (TDB) plans they typically replaced. Importantly for employers, cash balance plans reduce or eliminate interest rate risk (we discuss the significance of interest rate risk in TDBs in our article Plain Talk About Risk – To The Company).

For the typical cash balance plan, employers retain one key element of risk: matching the performance of trust assets to ‘interest credits’ under the plan. In what follows, we unpack this traditional cash balance plan risk, illustrating just how serious this risk – the mismatch between the plan’s interest credits and actual trust returns – can be. As we shall see, this risk is most problematic when interest rates are increasing and the yield curve is ‘steep.’

For purposes of this article, to illustrate traditional cash balance plan risk, we consider a fairly typical design — one that provides interest credits based on 10-year Treasury bond yields1 — and we observe the behavior of this design in the context of historical data since 1950.

Fundamental risk: mismatch between interest credits and trust returns

The fundamental risk presented by this cash balance plan is that it promises annual interest credits based on a long-term rate of return (the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds) that resets annually. If interest rates are static, buying and holding a 10-year Treasury bond would hedge this risk. But if interest rates go up, the value of the bond declines, generating a loss; if rates go down, the value of the bond increases, generating a gain.

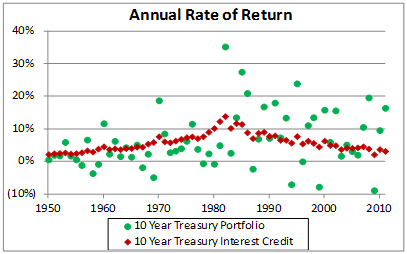

The chart below illustrates this point, showing annual cash balance interest crediting rates (red dots) based on the 10-year Treasury bond yield at the beginning of each year, along with annual rates of return (green dots) over the period 1950-2011 on a 10-year Treasury investment portfolio2. The difference between the green dots and red dots represent the gains and losses each year.

From year to year, the mismatch can be substantial, generating a one-year loss of as much as 13% (during 1994, when the 10-year Treasury yield increased 2.0%) and a one-year gain of as much as 21% (during 1982, when the 10-year Treasury yield decreased 3.6%).

The chart shows how bond returns (green dots) fluctuate substantially in response to changes in interest rates, while liabilities based on interest credits (red dots) hardly move as rates change (and their movement is in the opposite direction).

Long-term “direction” of interest rates

Simply put, given the strategy above (promise 10-year Treasury cash balance interest credits, invest in 10-year Treasury bonds), as interest rates fall, you make money, and as interest rates rise, you lose money.

The red dots tell the story of a single 62-year interest rate cycle. At the beginning of 1950, the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds was around 2%. Over the next 32 years, rates generally rose, reaching 14% by the end of 1981. And since then, rates have trended downward for 30 years, to less than 2% at the end of 2011.

Given this pattern for interest rates, it is not surprising that the green dots show three decades of predominantly low or negative returns (as interest rates rose) followed by three decades of predominantly high returns (as interest rates declined).

If we consider the pre-1982 and post-1981 experience separately, we see that the mismatch can persist for extremely long periods, producing two dramatically different stories.

During the more recent (post-1981) years, which spans the entire period under which cash balance plans have actually operated, the average (compound annual) return on 10-year Treasury bonds has been 9.6%, whereas the return based on 10-year Treasury interest credits was 6.6%. In this environment, in other words, cash balance sponsors would have enjoyed substantial gains (3% per year on average) using a 10-year Treasury bond portfolio.

For the period 1950-1981, on the other hand, 10-year Treasury bonds earned an average return of only 3.4%, while the 10-year Treasury interest credit returned 5.3% per year. During these years, in other words, sponsors would have suffered annual losses of 1.9% per year on average over the entire 32-year period.

The different experience under the identical strategy, over very long horizons, is astonishing, and it is all due to the simple fact that interest rates rose during the earlier period and fell during the more recent period.

Subsidy in traditional cash balance plan designs

Providing the yield on a long-term bond, which resets annually, on a one-year basis is in fact a subsidy from the employer to the employee. The market rate for a one-year investment is the 1-year Treasury yield. Any guaranteed interest credit in excess of this amount is not available in the market, so this excess (the difference in yield between the 1-year Treasury and the 10-year Treasury in our example) is a subsidy.

The value of the subsidy will fluctuate from year to year based on the spread between 1-year and 10-year Treasuries. Since 1950, this spread has averaged 0.9% per year.

For 2012, the spread/subsidy is 1.9%: the yield on 10-year Treasuries is 2% and the yield on 1-year Treasuries is 0.1%. So, the value of the subsidy is currently more than twice what it “normally” is. We think this is an unintuitive conclusion – despite the historically low interest credits currently provided by cash balance plans, the subsidy is historically high right now, and the risk of providing this promise is greater than normal.

Fixed minimum interest crediting rates

Some cash balance sponsors provide a floor on annual interest credits – a 4% minimum rate is not unusual. Such minimums were often added when rates were higher and the cost was considered minimal. For 2012, however (and perhaps for the next few years), a 4% minimum interest credit amounts to a subsidy of 3.9% of account balances each year. In other words, sponsors, in this case, are offering a guaranteed return to participants of 4% for 2012, when the only guarantee available in the market, the 1-year Treasury, currently yields 0.1%.

Is the subsidy in traditional cash balance plans a problem?

Subsidies are not necessarily bad. If you are crediting an above-market rate of return and getting credit from employees for doing so, then arguably the subsidy is just another element of compensation. But – as should be clear by now – the subsidy in a traditional cash balance plan is very opaque. We are skeptical that employers get credit for providing this subsidy that is anywhere near its cost. And a subsidy that you pay but don’t get credit for is a “bad subsidy.”

Subsidies, by definition, cannot be hedged. They can be paid for explicitly though. In our example, a sponsor could invest assets in 1-year Treasuries and make an additional contribution equal to 1.9% of account balances for 2012. No one would, of course, take this approach; it’s far too expensive. But any alternative, in essence, is a decision by the employer to finance the traditional cash balance interest credit subsidy implicitly by taking on investment risk.

Chasing the bogey

While the plan under consideration provides a subsidized, above-market interest credit to employees, the basis for the interest credit (10-year Treasury bonds) is a conservative investment which generates a modest interest crediting rate.

In our experience, most cash balance sponsors think about the promise this way – as a modest ‘investment bogey’ to try to ‘beat.’ Such a strategy may work – indeed, virtually any portfolio comprised of stocks and bonds would have beaten the bogey over the past 30 years.

Which is not to say it has always been a smooth ride. Cash balance sponsors with diversified portfolios who retain fresh memories of 2008, or recollections of 2000-02, are aware of the significant year-to-year risks of this strategy.

Bear in mind, too, that the recent experience has come against a backdrop of favorable ‘tailwinds’ in the form of declining interest rates, which have boosted returns on the fixed income portion of the portfolio. With rates at all-time lows, scope for additional gains on bonds is extremely limited. If rates move up in the years ahead, the bond tailwinds will become headwinds, the subsidy in traditional cash balance interest credits will become apparent, and the goal of beating the bogey, even over long periods of time, will be more difficult than in any environment cash balance sponsors have yet experienced.

* * *

Summarizing, for a typical cash balance plan:

Traditional cash balance sponsors face an insoluble asset/liability mismatch and inherent year-to-year volatility.

The mismatch arises because annual interest credits based on long-term yields that reset annually are a subsidy to employees, which, by definition, cannot be hedged.

The risk/subsidy may not be well understood by employers or appreciated by employees.

The only practical way of dealing with the mismatch is by taking on investment risk and trying to ‘beat the bogey’.

Declining interest rates over the past 30 years have produced gains to cash balance sponsors on bond investments, masking the subsidy and attendant risks inherent in the design, and making the bogey easier to reach.

In the current interest rate environment (historically low rates, large 1-10 year spread) the subsidy and risks are more evident. If interest rates rise, sponsors will face stiff headwinds, as the cost of the cash balance promise increases at the same time that the value of bonds in the portfolio declines.

What is a reasonable promise?

In view of this situation, it is fair to ask: why do employers sponsor these plans?

A typical answer might be: “If we beat the bogey, we reduce the cost of the plan.” For an employer with (a) the ability to absorb the year-to-year fluctuations that come with this strategy, (b) a long enough time horizon to ‘beat the bogey’ taking into consideration investment headwinds if interest rates increase, and (c) an employee population that values the stable, above-market interest credits provided under the plan, this design may make sense.

However, employers who prefer to reduce plan-related risk will want to reconsider the design of their cash balance plans – specifically, the design of the cash balance plan interest crediting rate.

The ReDB® alternative

The risk/subsidy we’ve discussed in this article is inherent in all long-term yield-based interest crediting rate designs. Historically, almost all cash balance plans credit these kinds of ‘above market’ rates, in accordance with IRS guidance.

In late 2014, however, IRS issued final regulations that allow plans to use market-based interest crediting rates – based on either the return on trust assets or a diversified mix of mutual funds. These market-based rates, used in what we call The ReDefined Benefit Plan® (ReDB®), do not saddle employers with the risk/subsidy we have discussed. Instead, they allow the provision of a truly DC-like benefit, where interest credits are aligned with asset returns and the asset/liability mismatch at the heart of the traditional cash balance design is reduced to insignificance.

ReDB® designs do provide a ‘capital preservation guarantee’ – participants’ benefits cannot be less than the sum of ‘pay credits’ provided under the plan. A crucial difference between ReDB® guarantees and the traditional cash balance interest credits, however, is that ReDB® guarantees are cumulative, whereas traditional guarantees are annual.

Under a traditional cash balance plan, the sponsor is exposed to losses on all participant accounts each year based on performance versus the interest credit in that year. For an individual participant, account balances grow over time, which means the risk of underperforming, in dollar terms, increases each year.

Cumulative guarantees don’t work like that. For these guarantees, the risk of a shortfall is greatest in the first few years, when account balances are small. Over a 10-year or longer horizon, the likelihood of achieving a positive investment return increases to a near-certainty.

* * *

Cash balance sponsors now have a choice about how much risk they want to take on. And this is an especially critical time to choose. Current interest rates suggest the traditional cash balance subsidy is larger than usual right now, particularly for plans with fixed minimum rates. And if interest rates rise over the next several years, traditional cash balance plans will become more expensive and painful for employers.

____________________

1Under IRS rules, plans can credit interest based on Treasury yields from 1 to 30 years. For plans that credit interest based on Treasuries that mature in less than 10 years, the risk is less pronounced than what is discussed here. Conversely, for plans that credit interest based on 30-year Treasury bond yields, the risk is even more significant.

2Mechanically, assets are invested in a 10-year Treasury bond at the beginning of the year, the mid-year coupon is reinvested at the June 30 6-month T-bill rate, the (now 9-year) bond is sold at year-end, and the assets are reinvested in a 10-year bond for the following year. No expenses are assumed.