Tax policy and retirement plans — a summary

Tax policy and retirement plans -- a summary

We have posted a series of articles separately analyzing the impact on 401(k) plan participants of possible changes in the Tax Code, including comprehensive tax reform proposals, proposals in connection with ‘solving’ the ‘fiscal cliff,’ caps on tax preferences, the new Medicare tax on net investment income and capital gains and dividend tax treatment.

In this article we synthesize those analyses. As a result, the numbers are going to change. In the prior articles we isolated the effect of changes in particular features of the Tax Code, e.g., the effect of an increase in capital gains tax rates. Now we are going to look at, e.g., the effect of an increase in capital gains tax rates together with a change in ordinary income tax rates and the new Medicare tax on net investment income.

We begin with a discussion of our basic methodology — calculating the value of a participant’s plan contribution vs. saving outside the plan, for a period of 10 years. We then consider the value of in-plan vs. out-of-plan savings under 2012 rules, taking all the key taxes — ordinary income, Medicare net investment income and capital gains and dividend taxes — into account. We then illustrate how the results would have changed had we gone over the ‘fiscal cliff’, triggering a broad range of tax increases. Finally, we consider the effect of a 28% cap on the 401(k) “tax preference” which continues to be a possibility under comprehensive tax reform proposals.

Methodology

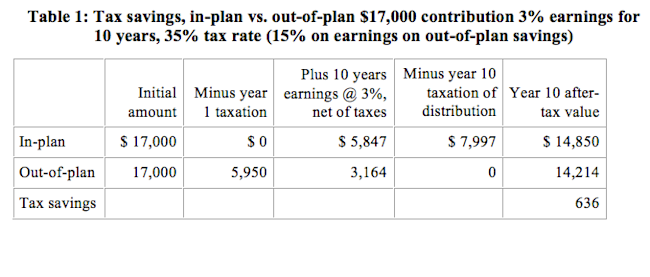

Our basic assumption is a taxpayer paying federal ordinary income taxes at the highest marginal rate, 35% for 2012. That participant is considering making the maximum contribution to a 401(k) plan — $17,000 in 2012 (ignoring catch up contributions available to those 50 and over). The contribution goes into a non-taxable trust. When the contribution and any trust earnings are paid out, the taxpayer pays taxes on the entire distribution at ordinary income tax rates.

Our question is: how much is the favorable tax treatment 401(k) plans get under the Tax Code worth to this participant? For our base case we assume that:

The taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is the same in the year of contribution and the year of payout.

The trust earns 3% per year.

The money remains in the trust for 10 years.

Under 2012 rules, the key tax rates that will affect this analysis are:

Ordinary income tax rate: 35%.

Capital gains tax rate: 15%.

Dividend tax rate: 15%.

As a general matter, we will ignore Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (Social Security and Medicare) taxes on wages. This is because FICA taxes are paid regardless of whether the participant saves in the plan or outside it, so they can be ignored for purposes of a comparative analysis of the value of 401(k) savings vs. out-of-plan savings (they do matter in comparing non-401(k) qualified plan benefits to ‘out-of-plan’ savings.) (Our next article, which looks at changes effective for 2013, will consider the impact of the new Medicare tax on net investment income for high-income taxpayers.)

Base case

For our base case, we will assume that the participant invests out-of-plan savings in capital gains-generating investments and that the full amount of capital gains is taxed each year at the (lower) capital gains rate (under current rules, you would get the same result if you invested in dividend producing stocks). (A “buy and hold” capital gains strategy — where no capital gains were realized until the end of the 10 year period — would produce a slightly better tax result for the out-of-plan saver.)

Thus, under current rules, and assuming that out-of-plan investments maximize capital gains treatment, the participant would be $636 better off if she saved through the plan rather than outside the plan.

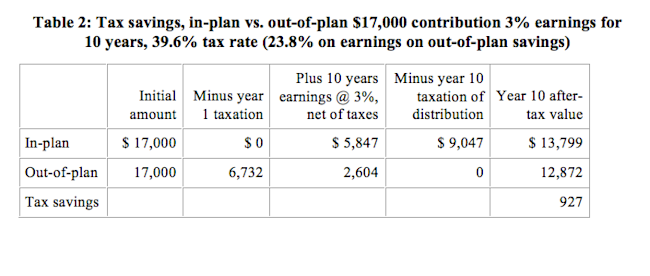

What might have been: the fiscal cliff

Now let’s consider what would have happened to the relative value of in-plan savings in 2013 if no action was taken to avoid the ‘fiscal cliff’:

Ordinary income tax rate: 39.6%.

Capital gains tax rate: 20%.

Dividend tax rate: 39.6%.

New Medicare tax on net investment income: 3.8% (for families making over $250,000); unlike the Medicare piece of FICA, this is a tax that is only paid on out-of-plan investments.

(We note that under the law passed in January, all of the changes above, except for the increase in dividend tax rates, do apply to high income taxpayers.)

Under these rule changes, the relative value of saving in the plan increases from $636 to $927. Thus, the higher tax rates that were set to take effect this year would have significantly increased the value of in-plan versus out-of-plan savings. (While it is not strictly relevant to this analysis of comparative tax value, it is worth noting that, while the relative tax benefit of saving in the plan goes up, the amount the participant has after 10 years of in-plan savings goes down by more than $1,000, from $14,850 to $13,799. Such is the bite of higher taxes generally)

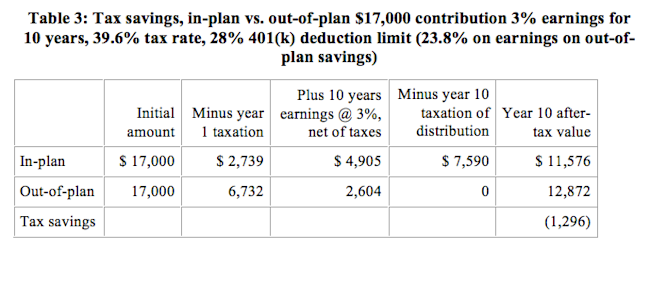

Impact of a tax preference cap

One tax effect these numbers do not capture is the impact of a cap on the 401(k) “tax preference.” Such a cap, e.g., the President’s proposal to cap at 28%, has been a feature of fiscal cliff negotiations and comprehensive tax reform proposals. Generally a cap would reduce the relative tax value of in-plan savings, and we provide the following analysis to illustrate a cap’s possible effect.

In our example, the $17,000 must fund both the contribution and the current taxes owed due to the deduction limit, and any amount ‘held back’ for taxes is itself taxed at the full 39.6% rate. The amount ‘held back’ to cover taxes, in our example, is $2,739 [$17,000 x (39.6% – 28%) / (1-28%)], leaving $14,261 available for ‘in-plan’ savings.

The table shows, based on the assumptions used, that a cap on 401(k) deductions could make ‘in-plan’ savings decidedly less attractive than ‘out-of-plan’ savings for high-income taxpayers, especially if they invest in capital gains producing investments.

* * *

As the foregoing makes plain, there are a variety of moving parts in this analysis, and changing one part can dramatically change the outcome. For instance, we have held the rate of return in all our examples constant at 3% and the term of investment (how long the money stays in the plan) constant at 10 years. Changing either of these variables will change the numbers. (Generally increasing the rate of return or the term will increase the relative value of in-plan savings.) While many of the ‘fiscal cliff’ tax increases have been deferred for 2013, they are re-emerging in discussions as part of a long-term solution of budgetary issues. We will continue to update you on this issue as events unfold.