The fiscal cliff and retirement plans: Medicare taxes

As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), for joint filers making over $250,000, Medicare taxes will increase beginning in 2013. This tax increase is part of the ‘fiscal cliff’, but there has been, generally, no discussion of, e.g., delaying the effective date of this new tax. The new tax will have the effect of increasing the relative value of saving in a 401(k) plan or other qualified plan.

In this article we review just how significant the impact the relative value of in-plan vs. non-plan savings may be.

Medicare taxes generally

Medicare taxes are a little complicated. First, a portion (pre-PPACA, half) of the tax is ‘paid’ by the employer, and half is paid by the employee. While it may be theoretically more accurate to treat both portions as paid by the employee, in this article we are strictly looking at the direct tax impact on the employee-participant, so we will only consider the direct tax on the employee. Second, Social Security taxes are paid only up to the Social Security Wage Base ($110,100 for 2012), while Medicare taxes are paid on all wages. Third, while 401(k) contributions are excluded from income tax when made, they are subject to Social Security/Medicare taxes.

Pre-PPACA, in 2012, the total Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (Social Security and Medicare) tax for the employee/participant is 7.65%. 1.45% of this is the Medicare tax. So the 2012 Medicare tax is 1.45% on all wages.

PPACA changes

PPACA changes the Medicare tax, beginning in 2013, making the analysis even more complicated. First, PPACA changes only apply to joint filers making over $250,000 per year. Second, the additional tax is paid only by the taxpayer – the employer does not pay an additional tax. And third, a new Medicare tax applies to investment income, not wages.

What are the new Medicare taxes? The PPACA increases the Medicare tax paid by the employee taxpayer by 0.9% of pay, from 1.45% to 2.35% (the “Additional Medicare Tax”). And it imposes a new tax on investment income of 3.8% (the “Net Investment Income Tax”). These new taxes only apply to joint filers making over $250,000 (that threshold is lower for single, head of household and married filing jointly taxpayers).

We have written several articles on the effect of possible Tax Code changes on the value of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. saving outside a 401(k) plan. In those articles we have focused strictly on income taxes and ignored FICA taxes. This is because money deferred into a 401(k) plan is still subject to FICA tax today. In other words, the 401(k) system does not allow for avoiding or deferring FICA taxes, only income taxes. (Note that this is different from ‘employer-provided’ qualified money, which is not subject to FICA tax.)

The upshot is that the increase in the Medicare payroll tax from 1.45% to 2.35%, or even the existence of this payroll tax at 1.45%, has no effect on a participant’s ‘in-plan vs. out of plan’ retirement savings decision. The new 3.8% Medicare net investment income tax, on the other hand, will reduce the growth of ‘out of plan’ savings, making ‘in plan’ savings more attractive.

Effect on participants

In what follows, we discuss the relative tax benefit of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. saving outside the plan. As in the prior analyses of tax effects we have, we assume the (high earner) participant contributes the 2012 maximum (ignoring catch up) of $17,000. We assume the participant leaves the money in the plan for 10 years and that in the plan it earns 3% per year. What is the value of that $17,000 after 10 years, net of taxes vs. paying taxes immediately and saving the remainder outside the plan?

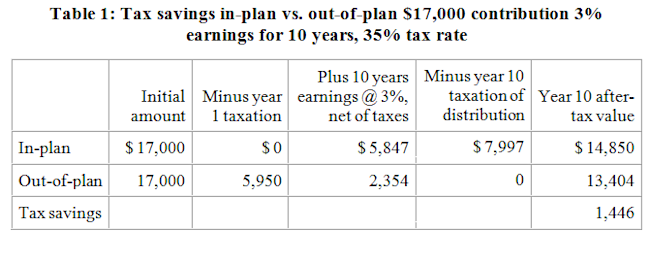

We begin with a baseline — the value of in-plan savings under current rules. Table 1 shows the tax saving (after 10 years) the participant realizes if he saves in the plan rather than outside of it. (For a full discussion of our methodology, see our article The ‘fiscal cliff’ and retirement plan participants.)

Bottom line, with these assumptions, under current tax rules, the participant has $1,446 more in 10 years than he would have had if he had saved outside the plan. The cost of Medicare payroll taxes, 1.45% under current law, is identical in both cases and they are therefore ignored.

Now, what happens when the new Medicare taxes are added on? The 1.45% initial tax goes up to 2.35% (we assume our employee taxpayer is over the $250,000 threshold), but again, this amount is owed irrespective of the 401(k) deferral decision, so it does not impact the analysis.

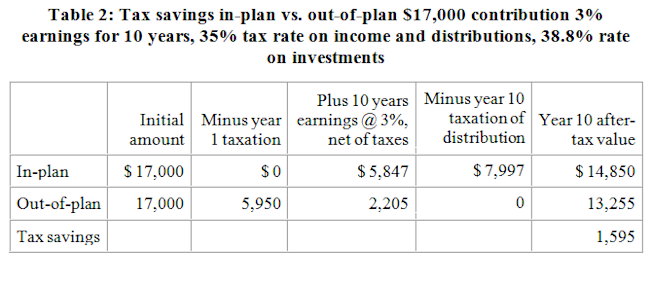

However, the new Medicare investment tax increases the tax rate on earnings for ‘out of plan’ savings from 35% to 38.8%. Table 2 shows the tax savings under these assumptions.

Thus, with the new Medicare taxes, the value of saving inside the plan increases by $149 or around 10%.

Implications

The 0.9% percent point increase in the Medicare tax for high earners, since it is owed whether money is deferred into a 401(k) plan or not, has no effect on the 401(k) decision. But the new 3.8% tax on net investment income for high earners is significant because it applies to ‘out of plan’ investments during the accumulation phase.

Our analysis to date has not taken into account tax favored investments (under current rules, e.g., capital gains and dividend income) that are available outside the plan and that may mitigate the net tax effect. We will consider these complications in our next article.

* * *

As we said at the beginning, these changes are likely to take effect no matter what Congress does with respect to the fiscal cliff. But their net impact cannot finally be evaluated until we understand what the rest of the Tax Code will look like. We will continue to update you on these issues.