De-risking in 2022 – Part 2 – the de-risking decision in the context of rising interest rates

As of February 2022, market interest rates are up significantly over 2021 rates.

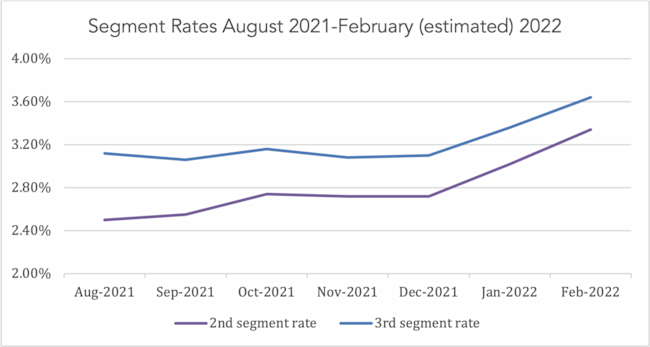

As we discuss in more detail below, many plans will use a 2021 August, September, October, November, or December lookback month to determine the interest rate to be used to value 2022 lump sums. For these plans, the increase in interest rates in 2022 will mean that 2022 lump sums will be valued at an interest rate that is lower than current market rates, generating a lump sum that is greater than the current market value of the associated liability.

In this article, we discuss how this situation, and certain other complicating factors that a sponsor may wish to consider, may affect the sponsor’s 2022 de-risking decision. We begin with some background on lump sum calculations.

Background – rules for calculating defined benefit plan lump sums

Generally, the interest rates used to value lump sums are the one-month first, second, and third segment rates applied under applicable ERISA plan funding rules. IRS regulations provide for a somewhat complicated system for deriving this rate the purpose of which is to make the discount rate more predictable and stable over time, so that participants will know in advance what discount rate will apply to them. To do this, the regulations provide for a “stability period” over which a pre-determined “lookback month” rate will apply.

The stability period is “the period for which the applicable interest rate remains constant.” There are five different stability period options: (1) one calendar month; (2) one plan quarter; (3) one calendar quarter; (4) one plan year; (5) or one calendar year. Simplifying, if the plan year is the calendar year, there are three options – a month, a quarter, or a year.

The lookback month is the first, second, third, fourth, or fifth full calendar month preceding the first day of the stability period. So, if the plan’s stability period is the calendar year, then the interest rate for, for instance, 2022, may be based on the rate for December, November, October, September, or August 2021.

A sponsor may change the stability period or lookback month, but there is a “grandfather” requirement: Generally, where there is such a change, the plan must provide that, for a period of one year beginning on the plan amendment’s effective date and ending one year after the later of its adoption date or effective date, a participant’s lump sum is determined using either the “old” interest/discount rate or the “new” interest/discount rate, whichever results in the larger distribution.

In our experience, a plurality of plans use a year-long stability period and a November lookback month.

Higher cost of 2022 lump sums relative to the (current) market

For plans using a year-long stability period and a November 2021 lookback month, the lump sum valuation interest rate for 2022 is 60 basis points lower than current rates.

To state the really obvious: lump sums paid out by such a plan, and any other plan using 2021 lump sum valuation rates that are lower than current rates, will be greater than they would be if they were paid out at current rates.

To illustrate this effect, as in our last article, we use the cost-of-benefit with respect to a terminated vested 50 year-old participant who is scheduled to receive an annual life annuity of $1,000 beginning at age 65. The amount paid to this participant using a November 2021 lookback month valuation rate would be $10,218. If it were done at current rates, it would be around $9,024.

If this relationship between (older, lower) lump sum valuation rates and current rates continues for the rest of 2022, three issues are raised: First, paying out a lump sum in 2023 will generally be a “better deal” for the sponsor than paying it out in 2022. Second, if a lump sum is paid out in 2022, the additional cost (resulting from the use of the older, lower valuation rate) may show up as an additional unfunded vested benefit for purposes of calculating 2023 PBGC variable-rate premiums, resulting in an increase in those premiums. And, third, such a payout is also likely to increase balance sheet net liabilities.

Annuity settlement as an alternative

In these conditions, one alternative a sponsor may consider is settling the liability by distributing an annuity rather than a lump sum. That is because annuities are priced at market rates rather than (as are lump sums) using 2021 lookback month rates.

This approach would generally not (at current rates) work with our example 50-year-old participant – we estimate that an annuity carrier would charge a 30% premium-over-book to settle that liability.

However, as a participant approaches retirement age, this premium-over-book would go down. Depending on the cost-over-book of the lump sum, an annuity might begin to be competitive for terminated vested participants over, e.g., age 60.

One critical issue with respect to pre-retirement annuity settlements is whether the plan provides any early retirement (or other) subsidies – these will generally increase the cost of an annuity settlement.

Variable-rate premium effects

With respect to 2022 lump sum settlements, if the lookback month interest rate used to value lump sums is lower than the valuation rate used for unfunded vested benefits (UVBs) for purposes of calculating PBGC variable-rate premiums, there may (if on that basis the plan is determined to have UVBs) be an increase in the 2023 variable-rate premiums.

We discuss the different methods used to value UVBs in our article Measuring UVBs for variable-rate premiums – the alternative vs. standard method election.

Financial disclosure effects

We have discussed financial disclosure effects in our articles on 2020 lump sum and annuity settlements and in our article Liability settlement, mark-to-market accounting, and PBGC premium reduction: effects on corporate earnings. We briefly note the following:

With respect to 2022 lump sum settlements, if the lookback month interest rate used to value lump sums is lower than the 2022 valuation rate used for plan disclosure, there will be an increase in the 2022 balance sheet net liability with respect to the plan. The same principle applies to annuity settlements at an amount higher than (what would have been) the year end value of the associated liability.

For sponsors with accumulated unrecognized experience losses (e.g., interest rate losses), settlement of a liability will trigger recognition of a (proportionate) share of those losses.

To a great extent, for many sponsors/plans, the critical issue is trend …

With respect to any settlement, there is, of course, always the risk of “settler’s remorse.” That is, e.g., if a liability is settled with an annuity at current rates, and rates then go up, there will be natural tendency to think “If we had just waited we could have gotten the annuity for less.” This risk is offset by the opposite one – “non-settler’s remorse” – triggered when rates go down.

The decision to de-risk is always colored by the sponsor’s view of interest rate trend. The historical trend in interest rates (arguably for the last 40 years) has been down. There is, of course, no way to predict (any better than the market is currently predicting) what rates will be a month from now, much less at year end.

This challenge is, for lump sums, somewhat mitigated by the lump sum calculation rules, especially for sponsors using a 12-month stability period. For, e.g., sponsors using a one year stability period, one variable – the “cost” of the lump sum – will remain constant for all of 2022 (because the valuation interest rate is fixed as of the beginning of the year). For the moment, at least, those lower lump sum valuation rates (relative to market rates) will bias some sponsors towards delaying de-risking.

* * *