The Tax Value of 401(k) Plans for Lower Paid Participants

In a series of recent articles we have reviewed the tax value of saving in a 401(k) plan (relative to saving outside a plan) and considered the effect on the 401(k) tax benefit of different changes in the tax law. Those articles have focused primarily on the tax value to higher paid plan participants, because most of the tax law changes that have been enacted (e.g., the recent ‘fiscal cliff’ legislation) or are being considered only affect higher paid participants.

In this article we focus on the tax value of 401(k) savings to lower paid participants. We do so not because there is a possibility of legislation that will ‘change the deal’ for them — such legislation is unlikely at this time — but because 401(k) plans in fact do provide significant tax benefits for lower paid employees, and that fact is not widely understood.

The misleading “headline tax benefit”

The problem of understanding the value of 401(k) plan tax benefits for lower paid employees was implicit in testimony given by William Gale of the Brookings Institution, before the Senate Finance Committee in 2011. In that testimony, which was highly critical of the current 401(k) system (and indeed proposed to replace the current system with a tax credit system), Gale consistently pointed to the fact that “existing tax rules provide less immediate benefit to low- and middle-income households.” (Emphasis added.)

The key word there is ‘immediate.’ A high margin (39.6%) taxpayer gets an ‘immediate tax benefit” of $396 for every $1,000 she puts into a 401(k) plan. A lower paid/lower margin (e.g., 15%) taxpayer only gets a $150 “immediate tax benefit’ for the same contribution. You could say that it literally costs the lower paid participant more to contribute to the plan than it costs the higher paid participant. That’s the headline tax benefit – big for high paid, not so big for low paid.

But determining the real tax benefit is a little more complicated than just looking at the value of the up-front tax exclusion. To determine the real tax benefit you have to consider the up-front tax exclusion plus the value of tax-deferred earnings (while the money remains in the plan) less taxation when the benefit is ultimately distributed. Let’s take a look at what that benefit is.

The actual tax benefit

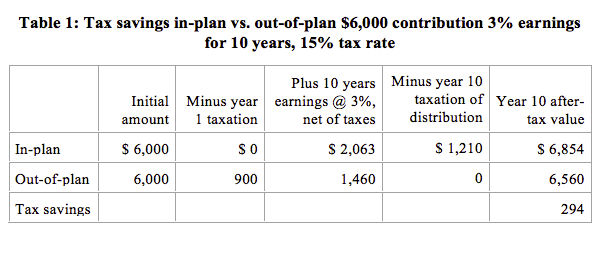

We have been using an analytical model that calculates the value of a participant’s plan contribution vs. saving outside the plan where money is contributed in year 1 and saved for a period of 10 years. For purposes of determining the relative tax value of 401(k) savings for lower paid participants we’ll use a participant in the 15% tax bracket who is considering making a contribution of $6,000 to a 401(k) plan. The plan contribution goes into a non-taxable trust. When the contribution and any trust earnings are paid out, the taxpayer pays taxes on the entire distribution at ordinary income tax rates.

Our question is: how much is the favorable tax treatment that 401(k) plans get under the Tax Code worth to this participant? To answer that question, we are going to compare how much the participant will have in 10 years if she saves inside the plan or outside the plan. Generally, we assume that:

The taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is the same in the year of contribution and the year of payout. As we said, we assume that rate is 15%.

The trust earns 3% per year.

The money remains in the trust for 10 years.

We assume that the participant invests out-of-plan savings in capital gains-generating investments and that the full amount of capital gains is taxed each year at the current capital gains rate, 15% for taxpayers who are not high earners. (A ‘buy and hold’ capital gains strategy — where no capital gains were realized until the end of the 10 year period — would produce a slightly better tax result for the out-of-plan saver.) We ignore Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (Social Security and Medicare) taxes (since FICA taxes are paid regardless of whether the participant saves in the plan or outside it).

Based on those assumptions, the following table shows the relative ‘tax value’ of saving inside a 401(k) plan.

So — after 10 years the tax benefit on $6,000 of savings is worth $294. That’s a relatively modest amount. But it’s not that much smaller than the tax benefit for a high earner; a high earner saving $6,000 gets a tax benefit (under our assumptions and under the post-fiscal cliff tax rules) of $327.

This example illustrates a couple of things. First, the tax benefit for in-plan savings is (almost) as great for lower paid participants as it is for higher paid participants. Second, given the ‘new normal’ of very low interest rates, the tax benefits for all participants are relatively low.

The impact of improved returns/longer “savings period”

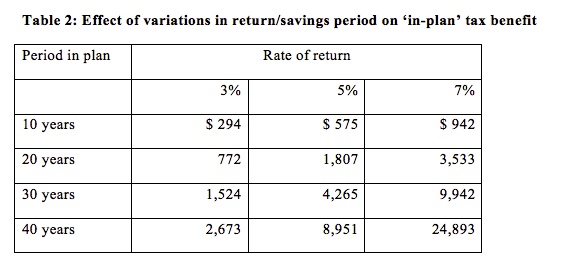

What happens if we assume a higher rate of return or a longer period of in-plan savings? The following table provides results for different return/savings period assumptions for the same sample participant ($6,000 initial deferral, 15% tax rate.)

As the numbers in the table show, the impact on the value of the tax benefit of improving returns and/or leaving savings in the plan longer is huge. In this context, it’s worth considering what effect, e.g., a reduction in fees of, say, 50 basis points per year might have.

Why are 401(k) tax benefits so significant for individuals who pay relatively low taxes?

Where you assume a taxpayer is in the same marginal tax bracket when he makes the contribution and he takes it out, the real tax benefit is the relative reduction in the taxation of trust earnings. Our low paid taxpayer is paying the same taxes on income and on capital gains – 15%. By saving inside the plan, he avoids, in effect, paying income tax rates on his earnings. And the more he earns, and the longer he leaves his money in the plan, the bigger that tax benefit is.

For the high-earner, the in-plan strategy exposes the entire account to taxation at ordinary income rates, which are higher than capital gains rates available for out-of plan investments. Indeed, prior to the 2013 tax increases on high-earners, the low paid taxpayer actually got a bigger tax benefit from in-plan savings than the higher paid taxpayer got.

Conclusion

As William Gale’s testimony implies, it seems that the ‘immediate’ tax benefit (which is relatively low for a low margin taxpayer) has more influence over participant savings decisions than the actual tax benefit does. That is a challenge for policymakers. It’s a challenge for sponsors too – to persuade lower paid participants that 401(k) savings are actually ‘worth it’ in saved taxes, to improve returns (a profound challenge in the current environment), and to encourage participants to start saving sooner and leave their money in the plan longer.