What would a 28% deduction cap mean for 401(k) tax benefits?

In our recent article The Administration’s 2014 budget: provisions affecting retirement benefits we discussed the Administration’s proposal to “limit the tax rate at which upper-income taxpayers can use itemized deductions and other tax preferences to reduce tax liability to a maximum of 28%.” Among other things, this cap would apply to the exclusion for 401(k)/defined contribution plan contributions. In that regard, the Budget states: “If a deduction or exclusion for contributions to retirement plans … is limited by this proposal, then the taxpayer’s basis will be adjusted to reflect the additional tax imposed.”In this article we provide a technical analysis of the effect – in reduced tax benefits – of such a cap.

Methodology

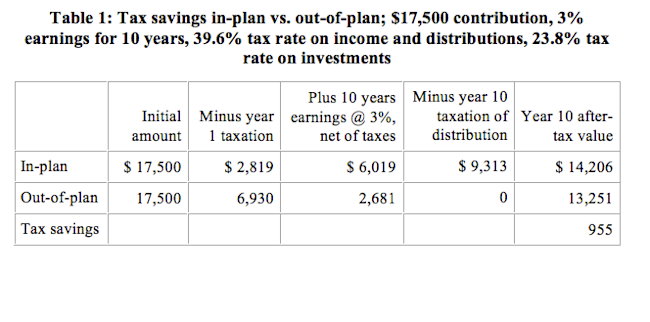

For purposes of comparing the net tax effect of the 28% ‘deduction cap’ we are going to use the methodology we have used in prior articles (see, for instance, our article How Much Does My 401(k) Plan Save Me In Taxes?). To determine the ‘tax value’ of qualified plan retirement saving, we calculate the value of a participant’s plan contribution vs. saving outside the plan, for a period of 10 years. We will look at a taxpayer paying federal ordinary income taxes at the highest marginal rate — 39.6%. That participant is considering making the maximum contribution to a 401(k) plan — $17,500 in 2013. The contribution goes into a non-taxable trust. When the contribution and any trust earnings are paid out, the taxpayer pays taxes on the entire distribution at ordinary income tax rates.

Our questions are, generally, how much is the favorable tax treatment that 401(k) plans get under the Tax Code worth to this participant, and, specifically, how does that treatment change when you cap the ‘inbound’ tax benefit (the exclusion from income) at 28%? To answer those questions, we are going to compare the relative value of the tax benefit under the current law (our ‘base case’) and under the ‘deduction cap’ proposal. Generally, we assume that:

– The taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is the same in the year of contribution and the year of payout.– The trust earns 3% per year.– The money remains in the trust for 10 years.

We assume that the participant invests ‘out of plan’ savings in capital gains-generating investments and that the full amount of capital gains is taxed each year at the (lower) capital gains rate (under current rules, you would get the same result if you invested in dividend producing stocks). (A ‘buy and hold’ capital gains strategy — where no capital gains were realized until the end of the 10 year period — would produce a slightly better tax result for the ‘out of plan’ saver.)

We ignore Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (Social Security and Medicare) taxes (since FICA taxes are paid regardless of whether the participant saves in the plan or outside it). We will have to consider, however, the new Medicare tax on net investment income.

Base case

Under current law rules, the key tax rates that affect the analysis are:

Top income tax rate: 39.6% (for families making more than $450,000).Capital gains and dividend tax rate: 20% (for families making more than $450,000).New Medicare tax on net investment income: 3.8% (for families making over $250,000).

The following table shows the relative value of saving in a 401(k) plan vs. outside the plan for taxpayers in this group.

Effect of a 28% cap on deductions

Calculating the effect of the deduction cap is, it turns out, very complicated. There are two issues: How do you account for the reduced deduction/exclusion? And how do you deal with the basis the participant gets?

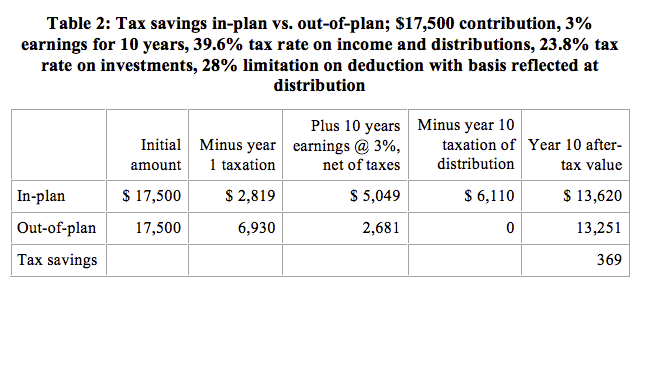

With respect to the first issue, our approach is to leave the participant with the identical basket of current-period consumption as under current rules. In other words, part of the $17,500 contributed to the 401(k) plan under current rules must be ‘held back’ to pay additional taxes today. And the amount ‘held back’ is itself subject to taxation at the full 39.6% rate. The amount ‘held back’ to cover taxes, in our example, is $2,819 [$17,500 x (39.6% – 28%) / (1-28%)], leaving $14,681 available for ‘in-plan’ savings.

Here is the math. The participant starts with $17,500. She contributes $14,681 of that to the plan. She pays tax at a rate of 11.6% on that $14,681 = $1,703. And she pays taxes on the amount ($17,500 minus $14,681 = $2,819) that she did not contribute to the plan at a 39.6% rate: 39.6% x $2,819 = $1,116. When you add up $14,681 (the contribution) plus $1,703 (the tax on the contribution) plus $1,116 (the tax on the part of the $17,500 that wasn’t contributed), you get $17,500. The analysis (and math) here is similar to that used to do tax gross-ups.

With respect to the calculation of basis, while it’s not entirely clear, we assume that a taxpayer’s basis in her account will equal the amount contributed ($14,681) times the tax rate that is paid (11.6%) divided by the actual tax rate (39.6%), or $4,300. This basis will reduce the tax liability associated with the 401(k) distribution.

That’s the methodology. Here are the numbers.

The value of the tax benefit goes from $955 to $369 — a 61% reduction in the tax value of in-plan savings resulting from the 28% deduction cap.

Impact

This rule would affect taxpayers in the three top tax brackets, 33%, 35%, and 39.6%. In 2013, the 33% bracket applies to joint filers making $223,051 or more and to single taxpayers making $183,251 or more. The effect on taxpayers in the 33% and 35% brackets is, obviously, less than the effect illustrated above for taxpayers in the 39.6% bracket.

To some extent, employers implement, and employees like, tax qualified plans because they provide significant tax benefits. There is some data indicating that this may be particularly true for 401(k) plans, which are targeted by this proposal (remember, this cap would not apply to DB plans). Those tax benefits are, obviously, most significant for high bracket taxpayers.

Thus, if the cap is adopted, it may not only reduce the tax benefits high bracket employees get out of 401(k) plans but also reduce employer and employee commitment to those plans.

* * *

The 28% ‘deduction cap’ isn’t just a cap on retirement savings. It affects “all itemized deductions, interest on tax-exempt bonds, employer-sponsored health insurance, deductions and income exclusions for employee retirement contributions, and certain above the line deductions,” and would (obviously) reduce the tax value of those other preferences as well. As such, it’s likely to encounter a lot of resistance in Congress, particularly Republicans.

We will continue to follow this issue.